Tangibility, Tactility & Texture

The following is based on the talk Tangibility, Tactility and Texture given by Luke Thompson at Push Conference 2016 in Munich, Germany.

Introduction

When creating an experience it’s important that every aspect should be considered and designed. At Kin, we don’t make a conscious divide between physical and digital interaction. We try to hone the blend between the two so that we can create more meaning in the work that we do. We want to augment screens and digital technologies; to bring them off walls and desks and use them as a more interesting material.

This talk is about Tangibility, Tactility, and Texture, and how the interactions we create have material choices and physical aspects that can be crafted to create better experiences.

Tangibility

Things Table

We all learn in different ways and process information best through multi sensory experiences. When we’re designing interactive installations and the delivery of digital content, it’s beneficial to consider a balance of sensory inputs. Learning through physical action and activity, or kinaesthetic learning, can be a great tool in getting your point across.

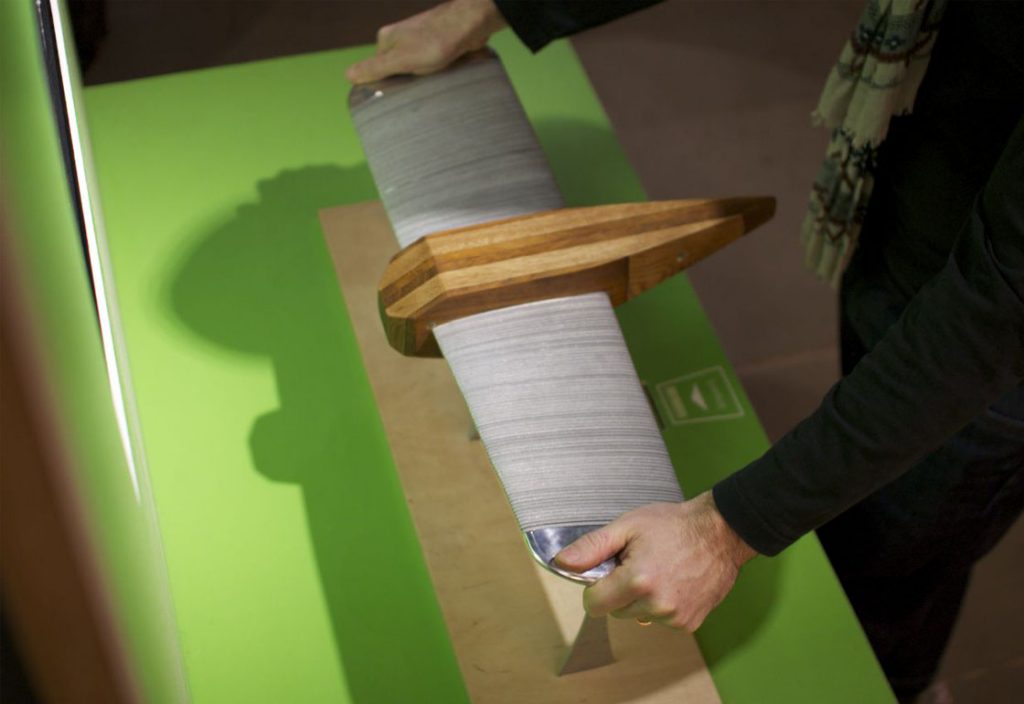

An example of this idea is the game controller we made for Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester. They wanted to communicate how the early experimental plane AVRO Type F manoeuvred using a unique twisting wing technique. Rather than using a standard gamepad we created a model of the plane where visitors manipulate the wings to fly a plane in the game. Not only is the model inviting to touch but it communicates a complex problem simply, making the engineering understandable through physical demonstration.

Design and Play – framing the experience

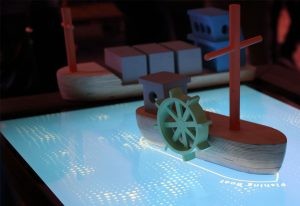

Boat Builder

We all explore the world around us through our sense of touch. Using materials and objects as part of our interaction design creates intuitive understanding of a subject or situation. When the concepts we’re communicating are complex, tangibility can help simplify them through physical demonstration. To keep people engaged and entertained we can use physical interactions to establish playful situations and encourage learning through experimentation.

Tactility

Tactility is about how we interact physically with digital content in order to replicate some of the physical properties and qualities of the analogue equivalent. So whilst we might not be directly touching things, there are other sensory phenomenon that can create a tactile experience.

The image here is a prototype of a video conferencing application that we were working on as part of a research project for a phone company. Whilst you’re not talking to the other person directly the experience of being face to face can still be brought into this digital experience. Tactility in this situation can be a simulation of something that happens in the physical world.

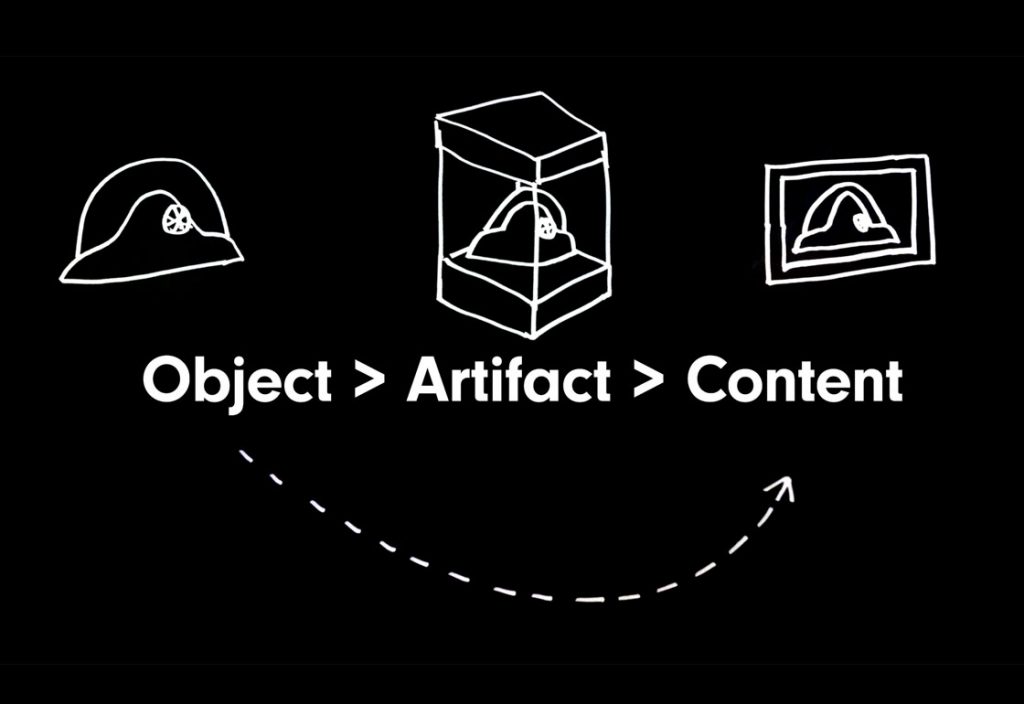

Using tactility as a tool can help work around the problems inherent to digital content. When an object starts life it has a function or a place in the world. For example, a hat – it keeps the rain out, or denotes status. But when a museum gets hold of it, it becomes an artifact. It’s been imbued with historical or cultural significance and now is behind glass. Now it’s not a hat, but ‘Nelson’s hat’. It can be seen in the museum space and inspected, but it’s lost some physicality as you can’t touch it. Often when we work with an object it’s become a piece of content. A digital image with very little physicality. In losing this physicality some context of how we can understand this object is lost. What we try to do is put some of the object back into this content.

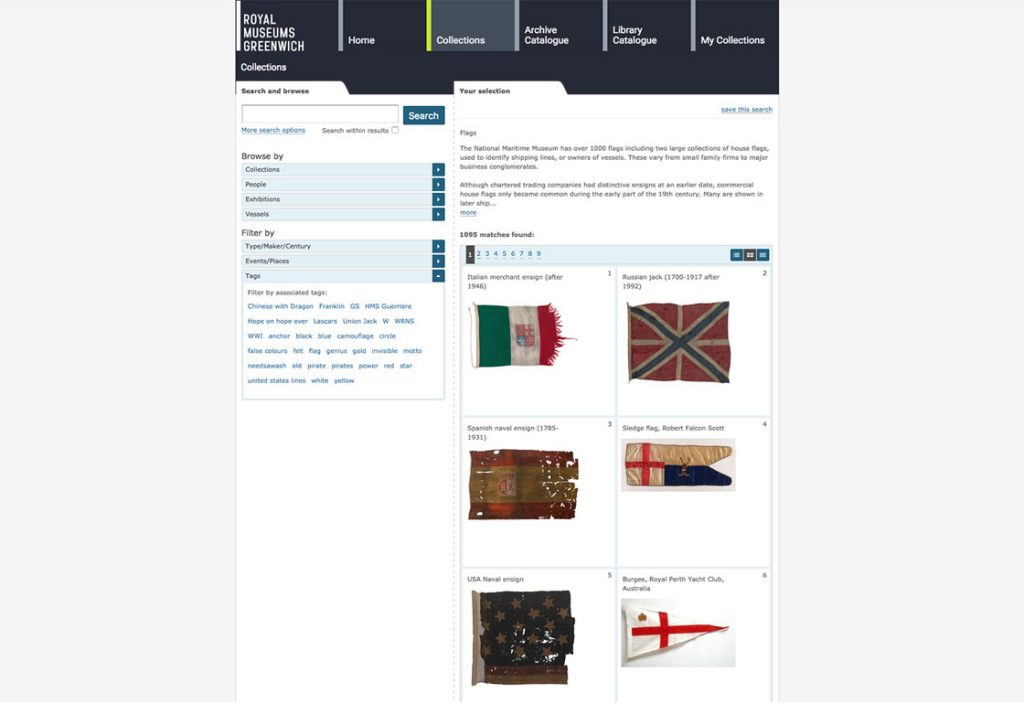

An example of this problem of object decontextualisation can be seen in the wild on the National Maritime Museum website. Their flag collection is excellent, but you can’t tell that one of these flags is larger than the others. Much larger. Really massive. So much bigger that it should be made clear when it sits next to the others in the archive: it’s extraordinary. It was captured from a Spanish warship (San Ildefonso) during the Battle of Trafalgar and it’s very difficult to imagine the size of boat this must have flown from.

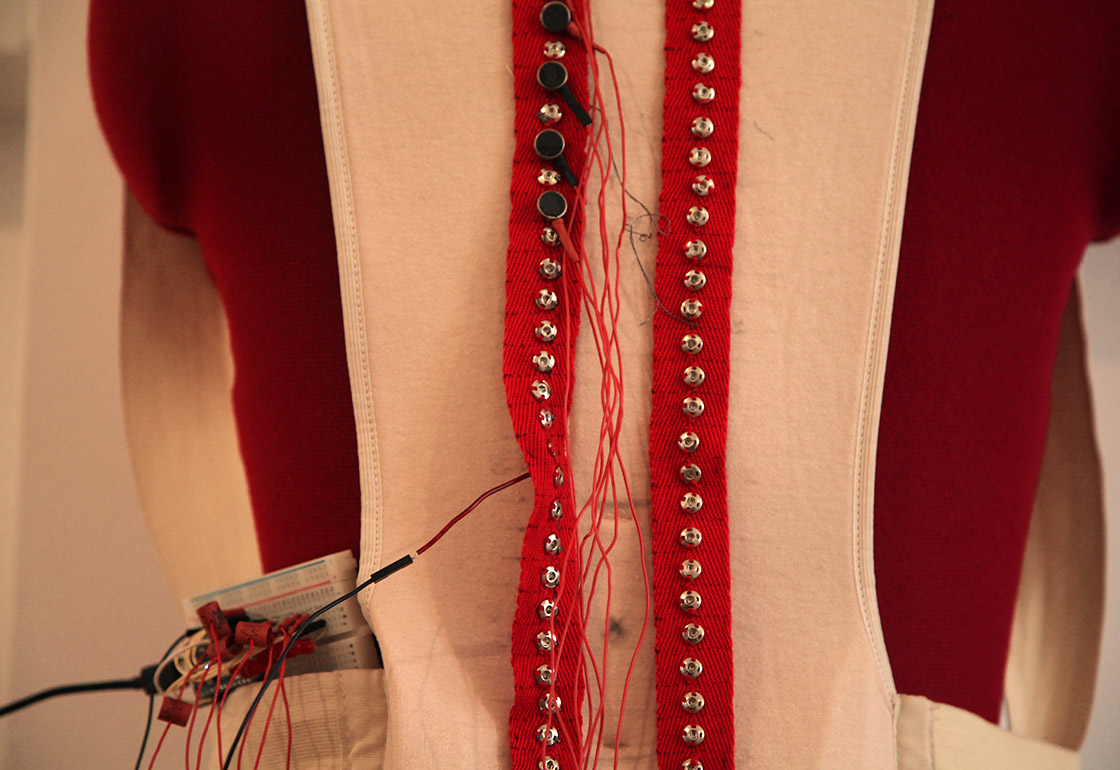

Lantern Slide Project

Tactility can be used to help digital content engage users by relating physical actions, properties and behaviours with things they understand in their lives and environments.

Texture

Materials have personality. They can be used to create technologically sophisticated work that’s also approachable. For a studio party we made up some LED throwies and put them in balloons. The effect is more magical than just balloons, and more fun than a pile of leds and batteries. It makes something inviting and engaging. (You can now buy balloons like this off the shelf and have become more commonplace.) The way technology is presented – how it looks and feels – could be considered it’s texture. It’s this texture that we’re interested in understanding and designing with.

In recent years the technology that most people have come into contact with is in the form of consumer electronics. Often ‘technology’ is bundled into this futuristic aesthetic; gloss black plastic, brushed aluminium, and gently pulsating sentient lights. Lots of product categories are moving away from this but an exemplar of the sector is external hard drives. They seem to want to hold on to the idea they have time travelled from some technologically advanced future – and are therefore far less likely to corrupt your files.

We want to create personable, human, and closer interactions but we need to use this sort of ‘technological’ equipment.

We often frames screens in wood. This cladding of technology in wood helps to make approachable digital interactives by stripping them of their futuristic qualities and allowing them to become part of the environment. More like furniture than consumer electronics. The wood contrasts against this idea of the alien hard drive from the future and situates the work now, again trying to make it more relevant to the user.

The Science Fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke came up with three laws. The third states: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

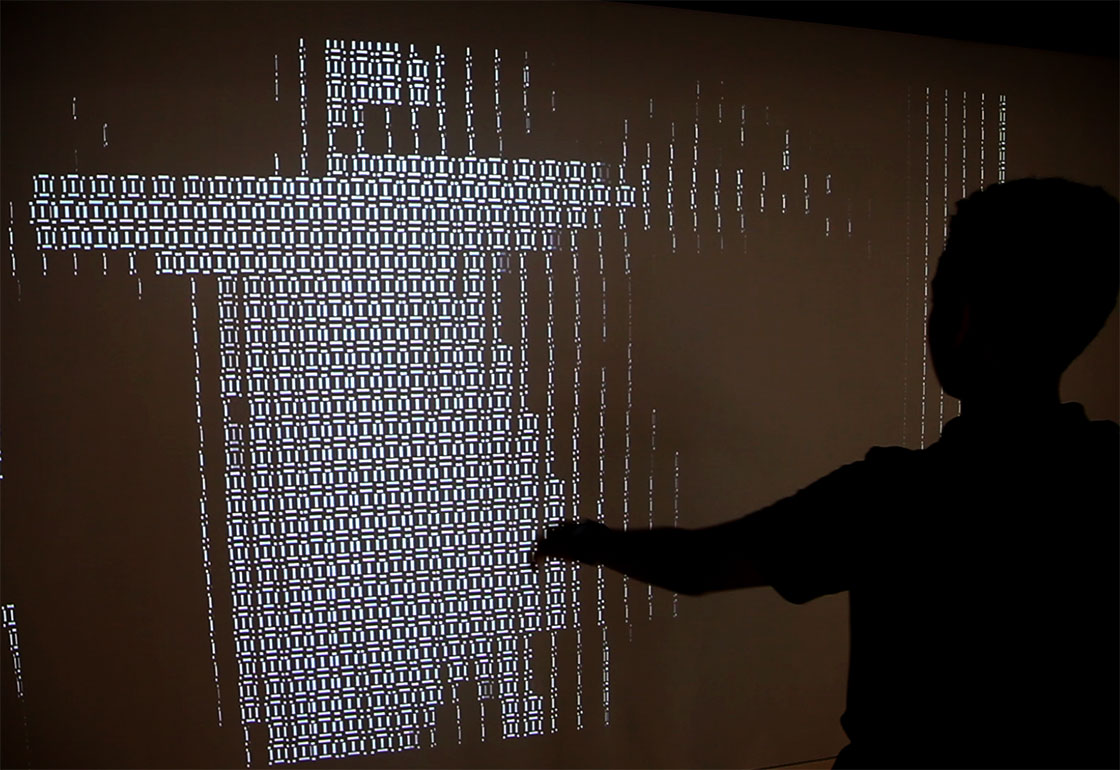

Google Barcoder

Texture is about how materials and thoughtful design can be used to make technology inviting and approachable. It’s about designing a whole experience that begins when the user steps through the door and extends into the sense of curiosity and magic it creates.

Conclusion

It doesn’t look like the digital world is going to overthrow the physical anytime soon. Rather than become extinct, vinyl records and books have increased their popularity , even if their status and reasons for being have shifted.

Screen technologies will perform less of a role with mobile devices plugging into everything to become the most functional screen we use. With the proliferation of embedded technologies and the ‘Internet of Things’ there will be more smart objects around than ever before. Virtual reality is going to need physical props before haptic technology becomes practical.

There will be increasing opportunities to explore and refine the gap between the physical and the digital and to use careful materials to create meaningful interactions.

It’s the designer’s responsibility to make sure we’re designing with the physical still in mind, to make it part of our tool box. At Kin we strive to put this into practice in our work and ‘get physical‘ wherever projects allow. We want to ensure we’ve considered the implications that tangibility, tactility and texture have on human interactions, communication and learning and how it can be used to make them better.